Clarence So, Chief Strategy Officer for Salesforce.com, opened last month’s Chief Strategy Officer Summit in San Francisco (by the IE Group) with a challenging statement: ‘Your strategy is nothing more than the sum of your tactics’. I found this to be less than satisfactory as an explanation, but considering the respect and influence Clarence engenders in the field, I kept an open mind about it. Clarence’s point is essentially that we do things, and we string these things together, and before you know it, in retrospect, we call the result a strategy.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Tom Kindem of BAE Systems presented a more traditional look at strategy by way of a military analogy (as would befit a defense contractor), the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE between Alexander the Great and Darius of Persia. But I still kept Clarence’s point of view in mind as Tom described Alexander’s “strategy” for defeating chariots – The Mouse Trap.

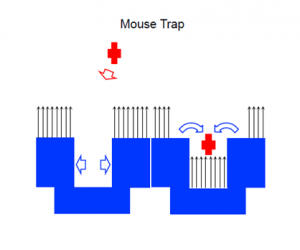

The execution of the Mouse Trap involves the center of the line raising their spears to vertical and retreating somewhat. The chariot horses will not charge a lowered spear, but will instead enter the U-shaped indentation in the front line, at which moment the spears will be lowered and ranks closed in from both sides, trapping the helpless charioteer. Perhaps Clarence was right – this Mouse Trap strategy looks like nothing more than the stringing together of a handful of spear-wielding infantry tactics, with the caveat that they are not random tactics, but appropriately and temporally ordered to achieve the objective at hand.

The execution of the Mouse Trap involves the center of the line raising their spears to vertical and retreating somewhat. The chariot horses will not charge a lowered spear, but will instead enter the U-shaped indentation in the front line, at which moment the spears will be lowered and ranks closed in from both sides, trapping the helpless charioteer. Perhaps Clarence was right – this Mouse Trap strategy looks like nothing more than the stringing together of a handful of spear-wielding infantry tactics, with the caveat that they are not random tactics, but appropriately and temporally ordered to achieve the objective at hand.

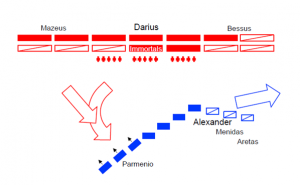

Tom then went on to describe the actual battle maneuvers, with Alexander opening the engagement with an echelon formation, left flank refused (tactic #1). Darius could not resist the flat, open ground, excellent for chariots, presented on the left and launched his main attack against this flank. Alexander kept a force engaged in the center to prevent Darius from splitting his lines (tactic #2), then began a flanking maneuver to the right (tactic #3). This drew out Darius’ right-side cavalry, creating a gap in the center of Darius’ main line, which Alexander then exploited by doubling back into the gap (tactic #4). Darius’ chariot driver was killed, Darius retreated with the rest of his army following, and the battle was subsequently won by Alexander via counterattack and pursuit.

Tom then went on to describe the actual battle maneuvers, with Alexander opening the engagement with an echelon formation, left flank refused (tactic #1). Darius could not resist the flat, open ground, excellent for chariots, presented on the left and launched his main attack against this flank. Alexander kept a force engaged in the center to prevent Darius from splitting his lines (tactic #2), then began a flanking maneuver to the right (tactic #3). This drew out Darius’ right-side cavalry, creating a gap in the center of Darius’ main line, which Alexander then exploited by doubling back into the gap (tactic #4). Darius’ chariot driver was killed, Darius retreated with the rest of his army following, and the battle was subsequently won by Alexander via counterattack and pursuit.

So was Alexander’s victory the result of 1) a properly executed series of tactics, 2) a properly executed strategy, or 3) being strategic? I’m going to make my case that the answer is #3, and by defining my terms attempt to show the differences between the approaches.

Often we do indeed find ourselves in an operating mode that is nothing more than a series of tactics strung together. This tends to be reactive on our part, when we find ourselves in uncharted territory, or in panic mode following a failed strategy and before we can properly implement a plan B or C or V, assuming we have one. It can also occur when communication breaks down and functional operating groups head off on their own. I liken this to a downhill, off-road bike race where tactically you avoid obstacles, take the jumps and traverse steep terrain, but without any overall plan in mind.

The sum of these tactics can become a strategy when they become part of a purposeful, deliberate plan. You have scouted the terrain and determined you will take that first boulder on your right side so as to better set yourself up for the tree that follows; you will take the jump cautiously because there is an opportunity to pass immediately upon landing, and so forth. You still take the terrain / market as a given, but when you have a strategy you are being proactive rather than reactive.

Being strategic, the third case, raises the stakes considerably. Being strategic means not just that you have “a” strategy, but that you have evaluated alternative strategies, that you have developed and evaluated multiple options and selected the best amongst the set (see “Strategy as a set of options”), that you have done some scenario planning under a varied set of assumptions. You have not only scouted the terrain but have mapped out alternate routes and are prepared to switch routes mid-race if circumstances so dictate, such as for wet weather or your competitor's maneuvers.

This definition of being strategic is significantly at odds with the view that strategy is the sum of your tactics, so much so as to make the two incompatible. Being strategic is necessarily proscriptive, compared with the retrospective, action-oriented nature of the latter, where strategy develops and unfolds in real time in the real world. A strategic approach, instead, involves planning and simulation in a virtual world, even if that be nothing more than spreadsheets and powerpoints, before it’s released for execution.

Being strategic could even be taken further, from taking the terrain / market as a given to disturbing and disrupting the terrain, as I discussed a couple of weeks ago in the Challenger Spirit focus of “Surfing the Disturbance”. Very, very few of us ever find ourselves in a position where we actually own the terrain / market and can remake it to suit our own goals (governments tend to label that “monopoly and restraint of trade”), but neither do we alwasy need to treat it passively and reactively. What Alexander knew was that Darius’ comfort zone was his reliance on his chariots, and that Darius would have no strategy that did not focus on those chariots, so Alexander disturbed the status quo by getting Darius to commit his chariots to a meaningless engagement on the left flank, out of harm’s way for his right flank double-cross.

Strategy, strategy, strategy; two days of strategy. It was all good, all very exciting, with the emphasis on innovation and disruptive technologies and discovery and insight and foresight and convergent versus divergent thinking. All very “yellow and green hat”, but with nary a “blue hat” to be found in the room, and by ‘blue hat’ I mean a focus on execution. When things go wrong strategically, it’s generally not that the strategy itself was wrong, but that it was poorly executed. If you mean to sail northwest, then generally you will manage to track somewhere between north and west allowing for frequent course corrections, but it’s the actual sailing that gives you the trouble. Strategies get out of alignment, over time they get disconnected from tactics and objectives, communication channels garble the message, and metrics often end up at odd with the overall strategy, incenting conflicting behaviors rather than reinforcing beneficial ones.

Strategy, strategy, strategy; two days of strategy. It was all good, all very exciting, with the emphasis on innovation and disruptive technologies and discovery and insight and foresight and convergent versus divergent thinking. All very “yellow and green hat”, but with nary a “blue hat” to be found in the room, and by ‘blue hat’ I mean a focus on execution. When things go wrong strategically, it’s generally not that the strategy itself was wrong, but that it was poorly executed. If you mean to sail northwest, then generally you will manage to track somewhere between north and west allowing for frequent course corrections, but it’s the actual sailing that gives you the trouble. Strategies get out of alignment, over time they get disconnected from tactics and objectives, communication channels garble the message, and metrics often end up at odd with the overall strategy, incenting conflicting behaviors rather than reinforcing beneficial ones.

This is why Kaplan and Norton’s Palladium Group puts such an emphasis on what they call the “execution premium”, or as their website puts it: “Strategy is important, but it is the execution that counts.” There is a demonstrable premium return on assets and profitability for organizations that can execute consistently.

What does it take to execute?

- Strategy management tools that enable proper strategy development prior to metrics generation to ensure alignment with objectives, not just what’s easy and available to report

- Business intelligence focuses on leading indicators, progress towards objectives, and drivers, not just final results, when it's too late to make a difference

- Business decision making is fact-based; Analytics becomes the basis for answering important questions

- Business intelligence provides data in context, facilitating communication and understanding, at all levels of decision making

Clarence and all the other speakers at the conference offered important, invaluable insights and made strategy sound like fun, but it takes a range of ‘hats’ and approaches to turn all of that wonderful innovation into bottom-line results. Jim Stikeleather, Chief Innovation Officer at Dell, summed it up best when he posited that thinking about the future (i.e. innovation) needs to be supported by structures, process, culture, business models and execution that create and extract value from innovative strategies.

6 Comments

Leo:

Excellant column with many things to consider. One key point that seems to permeate your discussion is the point of view of who is in charge. The discussion of strategy seems viewed from the eyes of senior management with various approaches to command and control.

In well run conflicts, victory is not dependent on senior commands view and ability to direct. Your example of Darius and his need to retreat leading to his defeat seems to reinforce this. When to US military executed Desert Storm it had excellent intelligence but still yielded command at the points of attack to the field commanders. They knew that rapid decision making at point of conatct was most important. They relied on their field commanders to make those decisions about what tactics would best achieve the objectives.

In this regards the system resembled John Boyd's OODA Loop approach (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). Strategy can seem like just a series of tactics when it is unified by deep understanding amoung all leaders as to the mission and purpose of the abjectives being sought. Your organization is much better at achieveing its objectives when you have embedded this ability to be adaptive in execution.

Your points about delegated authority, Steve, are doubly supported by Stephen Ambrose's excellent WWII books - "D-Day" and "Citizen Soldier", where he takes great pains to show how decision making authority in the hands of the mid-level officers, captains and majors, made a huge difference in the outcome of the D-Day invasion, especially when compared with more centralized command structure of the Axis. I don't like to overuse sports and military analogies, but that almost seems to be his motivation for writing those books - to show what an empowered organization can do. I especially like your concept of "adaptive execution" - I'm going to have to play with that and see what comes of it.

<>

Great point and often overlooked.

Strategy development is the fun part. It often involves offsite retreats, thought provoking questions, and engaging exercises. Everyone wants in. Strategy execution on the other hand can involve grinding work.

But the other reason for the lack of execution is that the traditional resource allocation process – commonly referred to as the budget or the annual plan – is separated from the strategic planning process. All the great ideas hatched in the strategy development sessions are forgotten about when it comes time to actually develop a budget.

While a lot has been said about rolling forecast replacing budgeting, the same fundamental disconnects exist. Unless an end-to-end process is developed, to go from strategy development right thru allocation of resources, don’t count on seeing your strategy executed.

“From order to cash” is a great example of an end-to-end process design. Let’s use that same holistic thinking to help build the strategy-to-execution bridge.

Pingback: A Strategy Management Tour de Force - Value Alley

Pingback: Dirt track date – Ecosystems and the networked economy - Value Alley

Pingback: Transformations – Personal and organizational - Value Alley